A Bumper Crop of Bagworms

- Jump To:

- References

There have been many reports this week about bagworms covering landscapes in several counties in northern and eastern Oklahoma. Like last year, the summer of 2021 is producing a “bumper crop” of this caterpillar pest. In this pest alert, I present information on the biology and life history of these caterpillar pests and focus on management in mid to late summer when medium to large larvae cause heavy feeding injury to host trees and shrubs.

Description: The common bagworm, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis, is found most frequently in its larval form, feeding on trees from within a silken bag it constructs from foliage and other plant tissues (hence, the insect’s common name) (Figs. 1A, B). Adult males are small moths with a black, hairy body and clear wings with a wingspan of about 1 inch (25 mm) (Fig. 1B). Adult females are wingless and have no functional legs, eyes, or antennae, retaining features of larvae. The female’s body is soft, yellowish white, and practically naked except for a circle of woolly hairs at the posterior end of the abdomen. Females remain in their silken bags, where mating occurs and eggs are laid. Mature larvae are about 1 inch (25 mm) long and have a dark brown abdomen, while the head and thorax are white with black spots (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. The bagworm, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis: (A) Bagworm casing on juniper; (B) adult male moth; and (C) larva removed from bag. Photo credits: (A) Eric Rebek, Oklahoma State University, Bugwood.org; (B) Pennsylvania Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry, Bugwood.org; and (C) Eric Rebek, Oklahoma State University.

Distribution: Bagworms are found in most states east of the Rocky Mountains. This pest is most common from Pennsylvania to Nebraska and south to Florida and Texas. It is commonly encountered throughout Oklahoma.

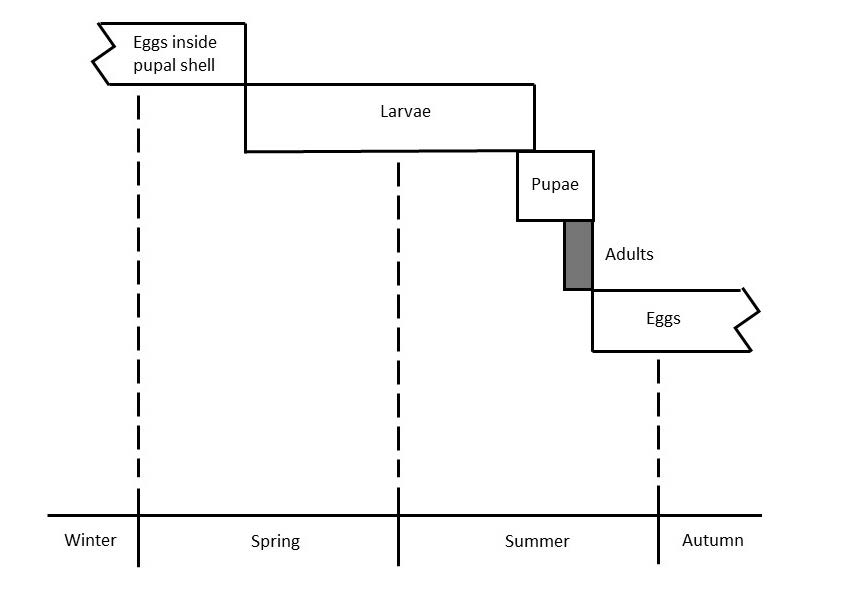

Life Cycle: Overwintered eggs are contained within the bags made by females from the previous

generation. Eggs begin to hatch in late April or early May and young larvae feed on

foliage and construct bags immediately. The first evidence of an infestation is normally

a small bag, about 1/4 inch (6.5 mm) long, standing almost on end. As larvae grow,

silk and fragments of the host plant foliage are added to the bag until it reaches

1.5 to 2 inches (38 to 51 mm) long. Mature larvae use silk produced from modified

salivary glands to fasten the bag to a plant stem. Pupation occurs in the bag in late

summer and males emerge late summer to early fall. They engage in a mating flight

in search of the wingless females, who remain inside their bags. Each newly mated

female lays between 500-1000 white eggs inside of old pupal cases. There is one generation

per year (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. General life cycle of bagworms. Adapted from Johnson and Lyon.

Hosts: In Oklahoma, the most common hosts are eastern redcedar, arborvitae, and other junipers. Bagworms will also feed on true cedars, pine, spruce, bald cypress, maple, boxelder, sycamore, willow, black locust, and oaks. Their host range includes about 130 different plant species in various parts of the United States. Reports out of northern and eastern Oklahoma this year include bagworms feeding and hanging from roses and hackberry (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Bagworms suspended by silken threads from upper tree canopy. Photo credit: Meg Counterman, Rogers County, Oklahoma.

Damage: Bagworm larvae damage their hosts by feeding on the foliage (Fig. 4). Dense infestations can completely defoliate small plants and heavy defoliation can kill hosts, especially evergreen trees and shrubs. Evergreens do not produce new foliage each year, so recovery from bagworm feeding can take years. Broadleaf hosts are not easily killed by bagworms, but they may be weakened and become more susceptible to certain woodboring insects and disease-causing plant pathogens.

Figure 4. Damage to juniper by bagworms. Photo credit: Eric Rebek, Oklahoma State University, Bugwood.org.

Management: Regardless of which season bagworms are encountered, infestations can be reduced or eliminated by removing bags by hand. The removed bags should be destroyed or discarded immediately, even in the winter because overwintering eggs within each bag remain viable. Bagworm cases can be disposed in the trash, but do not place them in compost piles or bins. When larvae become active in spring, bagworms can still be removed by hand if they are not too abundant, and the infested tree isn’t too tall. Do not climb trees or ladders to reach upper canopies just to remove bagworms. Call an International Society of Arboriculture (ISA)-certified arborist!

There are several naturally occurring parasitic and predatory wasps that attack bagworms. Certain fungal pathogens may play an important role in natural control of bagworms as well. The activity of these natural enemies at least partially explains the fluctuation in bagworm populations observed from year to year.

Chemical controls are most effective if applied early when larvae are small. In Oklahoma, it is normally a good practice to make insecticide applications by early June. Products containing Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (Bt), a bacterium that produces a toxin specific to caterpillars, are reported to provide good control of bagworms. Other effective reduced-risk products include those that contain the active ingredient spinosad (spinosyns A & D). Both active ingredients are most effective against small, young larvae, and they lose their effectiveness as larvae mature.

Mid to late season, large, older larvae are not as susceptible to Bt and spinosad as young larvae. Thus, bagworms must be sprayed with broad-spectrum, contact insecticides. Homeowners can look for products containing the active ingredients carbaryl (Sevin) or malathion that are labeled for caterpillar control on ornamental plants. As mentioned above, an ISA-certified arborist should be hired to combat bagworm infestations on large trees with tall canopies. Contact your county extension office for assistance with locating an ISA-certified arborist in your area.

References

Arnold, D., E. Rebek, T. Royer, P. Mulder, B. Kard. Major Horticultural and Household Insects of Oklahoma, Circular E-918. Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Oklahoma State University.

Hale, F., B. Klingeman, and K. Vail. The Bagworm and Its Control. University of Tennessee Extension Fact Sheet, SP341-U.

Johnson, W. T. and H. H. Lyon. Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs, Second Edition. Cornell University Press.