Ag Insights June 2024

Saturday, June 1, 2024

Native Grass Management

Josh Bushong, Area Extension Agronomist

To get the most out of native pastures, either for grazing or haying, management starts now. While inputs are typically low with native grasses, starting out with a soil sample, herbicide applications if needed, and grazing management should already be at the forefront of thought.

In most cases, only about 50 pounds of nitrogen will achieve optimal yields of about

1,500 pounds of forage. Additional nitrogen could produce more but usually isn’t economical.

If native grass stands are thin, weed control could be needed. Weeds are often the

result of mismanagement.

Annual haying is a common practice, but alternating haying and light grazing every

other year can be very beneficial. Early July is the optimum time of year to be haying

native grass pastures for hay. There are some basic production practices to maximize

production potential of these hay meadows. Since native hay meadows are a long-term

investment, they should be managed in such a way to sustain long-term productivity.

The most important management practice is cutting date. In most years, the optimum

cutting date will be between July 1 and 10. Harvesting native hay at this time will

achieve a good balance of forage yield and forage quality while also allowing the

native stand to recover the rest of the year to sustain production for following years.

The main key to managing any perennial hay field is to maintain a balance between

forage yield and forage quality. Time of cutting will be the primary production practice

that will determine the forage yield and quality. The maximum forage yield and maximum

forage quality hardly ever occur at the same time. Hay tonnage will typically peak

in late August, while crude protein and digestibility are usually highest in May.

The second most important management practice is proper cutting height. Cutting height

can easily be overlooked but can be highly detrimental to the life of the stand. Native

grasslands should never be cut shorter than 4 inches. Growing points on these grasses

are elevated during this time of year. If the growing point is cut off, then production

will be greatly reduced the following year.

Cutting height is also important because most of the native grass species need time

to re-grow to build root carbohydrate reserves. To sustain a native hay meadow, it

is recommended to only harvest it for hay once a year. Native grass species grow rapidly

through May and June but will exhibit slow re-growth in July after harvesting a hay

crop. In addition to the slow growth, the regrowth is often less palatable as well.

Native species have adapted through natural selection for these traits to ensure grazing

animals will not exhaust the root carbohydrates prior to winter dormancy.

Instead of a second cutting, grazing the regrowth late summer can be an option. If regrowth is limited or stands are struggling to recover, waiting for the first frost to graze will be the most beneficial. Adequate soil moisture is often the main limiting factor for how fast the regrowth occurs. Ideally grazing shouldn’t be initiated until the native grasses reach 15-18 inches in height. To acquire this height sooner, raising the cutting height at haying to 8 inches is recommended.

Field research conducted by Oklahoma State University has shown that forage tonnage

can be increased with an application of fertilizer in haying operations. However,

it is rarely economical to do so solely in grazing operations. When adequate moisture

is available during spring and early summer, 30-80 pounds of actual nitrogen fertilizer

can increase hay yield and crude protein. Herbicide applications are rarely warranted

on native grasslands. If managed properly, there should be a mix of native forbs and

legumes that benefit the grass production.

Some small plot studies conducted by OSU have shown an increase in grass production

is possible when broadleaf weeds (forbs) are controlled with an herbicide application.

However, increases varied depending on growing conditions and thickness of grass stand.

Previous mismanagement of the pasture often leads to thinner grass stands and more

weeds. Herbicides such as 2,4-D and/or dicamba are effective when applications are

made to small weeds. As weeds get bigger, more costly herbicides are often needed.

Good management practices include harvesting prior to mid-July, leaving at least 4

inches of stubble, harvesting only once during the growing season, and managing the

re-grown forage in the dormant season with either fire or grazing.

For more information about harvesting native grasslands for hay, contact your local

Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Office. Information can also be found

from the OSU factsheet “NREM-2891 Native Hay Meadow Management”.

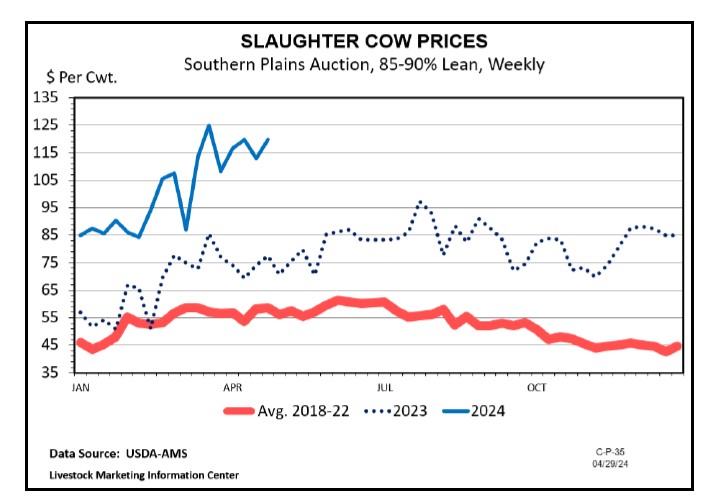

The Importance of Cull Cow Values

Scott Clawson, Area Ag Economics Specialist

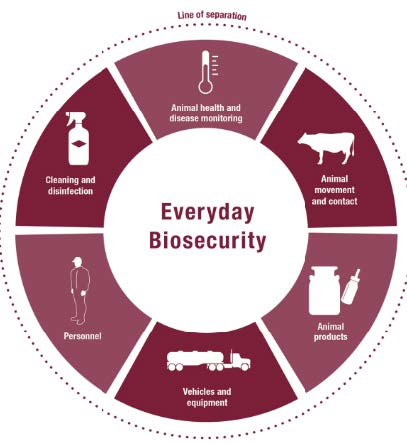

With beef, pork, and poultry exports playing a vital role in the economic health of livestock operations, producers need to understand the dangers that foreign animal diseases and other diseases may have on the viability of their operations. The recent discovery of Influenza A H5N1 virus in dairy cattle demonstrates the vulnerability of livestock operations to disease events. Sick animals are not the only consequence of a disease outbreak. The economic cost associated with disease can be high. Also, in foreign animal disease outbreaks, export markets can be temporarily lost. Currently, Columbia has restricted fresh/frozen beef and beef products from states with dairy herds testing positive for Avian Influenza. The best defense against these threats is a good biosecurity plan.

A recent survey of Oklahoma Cow/calf producers revealed that 31% of the respondents had never heard of biosecurity. The Oklahoma State University Beef Cattle Manual defines biosecurity as the development and implementation of management procedures to reduce or prevent unwanted threats from entering a herd or flock, as well as limiting or preventing the spread of disease within the ranching operation. Biosecurity is one of the best disease prevention methods available to livestock producers, but it can be a challenge to implement. Once implemented, the challenge is to remain vigilant in adhering to the protocol. When reviewing the 2014-2015 High Pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak, failure to follow biosecurity protocol was the main reason given for the spread of the virus. To have any realistic chance of a biosecurity program being successful, all parties involved in the operation must be willing to fully participate. If one person fails to comply with the protocol, the program is doomed to fail.

According to Beef Quality Assurance, the first step to developing a biosecurity plan

is to form a resource group. The group should include individuals important to the

success of the operation. One important person in this group is the biosecurity manager.

The biosecurity manager along with other individuals such as ranch workers, veterinarians,

nutritionist, and extension specialist will be tasked with determining the disease

risks of the operation as well a writing the biosecurity plan. Once the plan is written,

the biosecurity manager will be responsible for implementation and compliance with

the biosecurity protocols.

Biosecurity can be broken down into four basic areas which include traffic, isolation,

sanitation, and husbandry. Livestock producers must attempt to control traffic in

their operation. Livestock operations should have a line of separation (LOS). For

ranches, this would be the perimeter fence. All entry points to the ranch need to

be clearly marked with “Do Not Enter” signs. Producers should not allow anyone or

any animals to cross the LOS unless it is absolutely necessary.

Preventing wildlife from crossing the LOS is very difficult. Still livestock producers

can implement some management practices that should discourage wildlife from entering

the ranch. Sanitation practices such as keeping the ranch clean and free of brush

will discourage wild animals. Also, feed should be kept in feed bins or storage containers

to prevent attracting wild animals. Any feed spills should be cleaned immediately

to avoid attracting wildlife. Rodents and insects should be controlled. Livestock

producers who encounter issues with migratory waterfowl should contact the Oklahoma

Wildlife Department for help.

Obviously, newly purchased animals will need to cross the LOS. However, all new animals

need to be isolated for a minimum of 30 days and observed for any signs of illness

before being added to the herd. During isolation, the cattle should be tested for

specific diseases and vaccinated according to the ranch’s herd health program. Any

animal testing positive for disease and/or exhibiting disease symptoms should not

be introduced to the herd. In addition to newly purchased animals, show animals should

be placed in isolation upon returning from an exhibition. Also, any animal in the

herd that shows signs of illness needs to be isolated. Once the animal is completely

healed, then the animal can be returned to the herd.

Sanitation should be a top priority in all operations. All food and water troughs

should be kept clean. Pens, stalls, and barns should be kept free of manure build

up. If equipment such as a front-end loader is used for dual purposes such as manure

management and feeding, it needs to be cleaned and disinfected between jobs. Avoid

borrowing equipment from neighbors. If it is necessary to borrow some item, producers

should clean and disinfect it before and after using it. Feeding and haying areas

should be moved regularly to prevent manure build up. After traveling to shows, fairs,

or livestock auctions, trucks and trailers should be washed and disinfected. All show

equipment needs to be cleaned and disinfected after being used. Maintaining a clean

environment for your animals will go a long way in preventing diseases.

Animals that are provided with good care are more likely to remain healthy and resist

infections. Animals need a good source of clean water. Their nutritional needs should

be met. They should be provided with protection from harsh environmental conditions.

It may sound unnecessary to mention but all livestock owners should be familiar with

normal animal behavior. Any deviation from normal behavior should be investigated.

They should know the warning signs of an infection. Most importantly, they should

report any unusually large numbers of sick or dead animals to their veterinarian,

or state veterinarian.

No one expected to find Influenza A H5N1 virus in dairy cattle. This is a reminder

to livestock producers to be vigilant in following their biosecurity plan. Producers

that need more information about developing a biosecurity plan should contact their

local Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Ag Educator. Also, biosecurity

information is available at Beef Quality Assurance, The Center for Food Security and Public Health, and Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture.

Biosecurity

Barry Whitworth, DVM Senior Extension Specialist/BQA State Coordinator, Department of Animal & Food Sciences, Freguson College of Agriculture

With beef, pork, and poultry exports playing a vital role in the economic health of livestock operations, producers need to understand the dangers that foreign animal diseases and other diseases may have on the viability of their operations. The recent discovery of Influenza A H5N1 virus in dairy cattle demonstrates the vulnerability of livestock operations to disease events. Sick animals are not the only consequence of a disease outbreak. The economic cost associated with disease can be high. Also, in foreign animal disease outbreaks, export markets can be temporarily lost. Currently, Columbia has restricted fresh/frozen beef and beef products from states with dairy herds testing positive for Avian Influenza. The best defense against these threats is a good biosecurity plan.

A recent survey of Oklahoma Cow/calf producers revealed that 31% of the respondents had never heard of biosecurity. The Oklahoma State University Beef Cattle Manual defines biosecurity as the development and implementation of management procedures to reduce or prevent unwanted threats from entering a herd or flock, as well as limiting or preventing the spread of disease within the ranching operation. Biosecurity is one of the best disease prevention methods available to livestock producers, but it can be a challenge to implement. Once implemented, the challenge is to remain vigilant in adhering to the protocol. When reviewing the 2014-2015 High Pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak, failure to follow biosecurity protocol was the main reason given for the spread of the virus. To have any realistic chance of a biosecurity program being successful, all parties involved in the operation must be willing to fully participate. If one person fails to comply with the protocol, the program is doomed to fail.

According to Beef Quality Assurance, the first step to developing a biosecurity plan

is to form a resource group. The group should include individuals important to the

success of the operation. One important person in this group is the biosecurity manager.

The biosecurity manager along with other individuals such as ranch workers, veterinarians,

nutritionist, and extension specialists will be tasked with determining the disease

risks of the operation as well as writing the biosecurity plan. Once the plan is written,

the biosecurity manager will be responsible for implementation and compliance with

the biosecurity protocols.

Biosecurity can be broken down into four basic areas which include traffic, isolation,

sanitation, and husbandry. Livestock producers must attempt to control traffic in

their operation. Livestock operations should have a line of separation (LOS). For

ranches, this would be the perimeter fence. All entry points to the ranch need to

be clearly marked with “Do Not Enter” signs.

Producers should not allow anyone or any animals to cross the LOS unless it is absolutely necessary.

Preventing wildlife from crossing the LOS is very difficult. Still livestock producers

can implement some management practices that should discourage wildlife from entering

the ranch. Sanitation practices such as keeping the ranch clean and free of brush

will discourage wild animals. Also, feed should be kept in feed bins or storage containers

to prevent attracting wild animals. Any feed spills should be cleaned immediately

to avoid attracting wildlife. Rodents and insects should be controlled. Livestock

producers who encounter issues with migratory waterfowl should contact the Oklahoma

Wildlife Department for help.

Obviously, newly purchased animals will need to cross the LOS. However, all new animals

need to be isolated for a minimum of 30 days and observed for any signs of illness

before being added to the herd. During isolation, the cattle should be tested for

specific diseases and vaccinated according to the ranch’s herd health program. Any

animal testing positive for disease and/or exhibiting disease symptoms should not

be introduced to the herd. In addition to newly purchased animals, show animals should

be placed in isolation upon returning from an exhibition. Also, any animal in the

herd that shows signs of illness needs to be isolated. Once the animal is completely

healed, then the animal can be returned to the herd.

Sanitation should be a top priority in all operations. All food and water troughs

should be kept clean. Pens, stalls, and barns should be kept free of manure build

up. If equipment such as a front-end loader is used for dual purposes such as manure

management and feeding, it needs to be cleaned and disinfected between jobs. Avoid

borrowing equipment from neighbors. If it is necessary to borrow some item, producers

should clean and disinfect it before and after using it. Feeding and haying areas

should be moved regularly to prevent manure build up. After traveling to shows, fairs,

or livestock auctions, trucks and trailers should be washed and disinfected. All show

equipment needs to be cleaned and disinfected after being used. Maintaining a clean

environment for your animals will go a long way in preventing diseases.

Animals that are provided with good care are more likely to remain healthy and resist

infections. Animals need a good source of clean water. Their nutritional needs should

be met. They should be provided with protection from harsh environmental conditions.

It may sound unnecessary to mention but all livestock owners should be familiar with

normal animal behavior. Any deviation from normal behavior should be investigated.

They should know the warning signs of an infection. Most importantly, they should

report any unusually large numbers of sick or dead animals to their veterinarian,

or state veterinarian.

No one expected to find Influenza A H5N1 virus in dairy cattle. This is a reminder

to livestock producers to be vigilant in following their biosecurity plan. Producers

that need more information about developing a biosecurity plan should contact their

local Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Ag Educator. Also, biosecurity

information is available at Beef Quality Assurance, The Center for Food Security and Public Health, and Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture.

Double-crop Soybean Weed Management

Josh Bushong, Area Extension Agronomist

One of the first questions wheat farmers should ask themselves is what herbicides have been applied in their fields. Common wheat herbicides, namely group 2 ‘SU’ or ‘IMI’ products can persist in the soil for up to 36 months. The Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service has a new factsheet “Wheat Herbicide Rotation Restrictions to Soybean in Oklahoma, PSS-2798” that provides details to many of these common herbicides.

Starting soybeans off weed free is always ideal. Even if a harvest aid was applied

to get the wheat crop off, additional herbicide applications may be needed to clean

up weeds that were hard to get below the wheat canopy or even large, rank weeds like

crabgrass, pigweeds, and marestail. Regrowth on weeds like marestail is often an issue.

Even if the wheat field is clean of weeds at harvest, once sunlight reaches the soil

many of the summer weeds will germinate.

When applying herbicides during high temperatures weed control can be reduced. Systemic

herbicides such as glyphosate and grass products like clethodim need actively growing

plants for them to work. As temperatures go above 85°F, the plants begin to slow or

stop metabolic processes that move herbicides through the plant. Avoiding applications

during the heat of the day is recommended.

Certain herbicide programs may seem expensive but can still be economical if yields

are protected. From soybean emergence to the V3 growth stage (third trifoliate) is

the most critical period to limit weed competition to protect yield potential. For

most double-crop soybean fields, at least two herbicide applications are made. Once

at pre-plant and the other at early postemergence.

In addition to the herbicide traits that allow the postemergence applications of glyphosate,

glufosinate, 2,4-D, or dicamba there are still other options to consider. ALS herbicides

(such as Classic, FirstRate, and Pursuit) have good activity on many broadleaf weeds

but can be weak on pigweeds and waterhemp. PPO herbicides (such as Cadet, Cobra, Reflex,

Resource, and UltraBlazer) have activity on many problem broadleaf weeds and have

also been a good option if some weeds are suspect of ALS resistance. Assure II, Fusilade

DX, Poast and Select are some good options if grass control is needed.

As mentioned earlier, high temperatures at the time of application can reduce weed

control but it can also result in more crop response. Contact products such as Cobra,

Liberty, or Reflex can cause crop injury when applied during hot and humid conditions.

Also be aware that group 4 herbicides such as 2,4-D and dicamba become more volatile

as temperatures rise.

Only relying on postemerge (“over-the-top” or “in-season”) herbicide products limits

options and will tend to lead to herbicide resistance sooner. Options are limited

especially if applications are delayed due to weather events or breakdowns as weeds

become rank and less controllable. A more robust management plan includes preemerge

products with residual activity. This may not be as cheap as some of the postemerge

products but will provide more modes of actions, act as a safety net in case of delayed

post applications, and ultimately should provide much less weed competition early

on in the season.

Preemerge products can be applied preplant, prior to crop emergence, and some can be tank mixed with early postemerge products. Preemerge products need to be applied to the soil before germination of the weeds. In no-till production, some products can remain in the previous crop residue and control can be reduced. Some products need to be incorporated into the soil with rain or irrigation to become active. Preemerge and some postemerge products can provide residual soil activity.

Late planted soybeans will often benefit from narrower row spacing. In addition to

increasing yield potential, narrower rows will also have a better potential to canopy

sooner to prevent weed emergence. Late planted soybeans typically won’t be as tall

and will have fewer nodes, so yield potential can be improved by increasing seeding

rates.

To find out more information, contact your local OSU County Extension Office to visit

with your Ag Extension Educator and review the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service

factsheet PSS-2794, Meshing Soybean Weed Management with Agronomic Practices in Oklahoma

and PSS-2195, What if Engenia FeXapan or Xtendimax are Not an Option for Soybean Weed

Control.

Resistance in Livestock Products

Dana Zook, NW OK Area Livestock Specialist

It seems resistance is a term that comes up a lot these days. I have attended several field days and in-service trainings and I couldn’t help but notice how much OSU researchers are focusing on the topic of resistance. Some of the discussions were positive, discussing the development of disease resistant crops. Others held a slightly concerning tone when discussing the issue of parasites resistant to our anthelmintic (dewormer) products. In this article, I would like to focus on resistance that is present in our livestock operations and changes we can make to prevent further development in the future.

To set the tone, let’s review the basic definition of resistance. The Merriam-Webster

Dictionary defines resistance as “the act or insistence of resisting: opposition”.

There are several more definitions but the one that I think relates most to our industry

is “the capacity of a species or strain of microorganism to survive exposure to a

toxic agent (such as a drug) formerly effective against it”. The reality is that resistance

to some common products can develop quietly if we aren’t diligent about what products

we use and how they are applied. Interested in learning more? Read on.

In the livestock industry, resistance is prevalent in the type of parasites and insects

that can produce several generations within a season. Some facts of resistance in

the livestock industry are:

- Some internal parasites are developing resistance to many classes of anthelmintics (dewormers).

- Because of the short generation interval, horn flies can develop resistance within one season to chemicals in pour-ons, sprays, and ear tags.

- When weights are not taken, animals can be underdosed with dewormers or fly control products. This exposes target parasites to a less than effective dose.

- Resistance can develop if the same products (or chemical classes) are used year after year.

Resistance is widespread but there are ways to prevent further resistance from developing:

- Consult your veterinarian to see if your herd needs a deworming product. Manure samples can be collected to determine a fecal egg count within the sample. Taking this a step further, a fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) can be used to determine how well the deworming products are working. By doing this, producers may find some classes of cattle are more tolerant to internal parasites or that certain areas of the state may not need to be deworming cattle as often.

- Always rotate chemical classes when managing both internal and external parasites. Just alternating a product with a different name does not ensure it is from a different chemical class.

- Remove spent fly tags from animals in the fall. They may not contain enough chemical to be effective but the small amount that is left may allow flies to develop resistance before the next season.

These are just a few examples where resistance is occurring and how livestock producers can prevent further resistance development. I won’t attempt to discuss resistance within the area of Agronomy but examples in that industry are also prevalent. It’s important to look to our veterinarians, crop advisors, chemical salesman, veterinary supply stores, and OSU Extension Educators to help choose the right products for our operations. In the livestock area specifically, there hasn’t been a new chemical class developed for deworming in approximately 40 years. New product development is limited and the products we have now may be the only ones that are available long term. For this reason, it is imperative we keep them effective.

This summer, I am encouraging producers to consider how to prevent the development of resistance in the areas of internal and external parasite control. For more insight on this subject, check out a recent Extension Experience Podcast episode called “Got Worms? Dewormer Resistance with Dr. John Gilliam”.